Beyond the Vāra: Mastering Horā Variations (The Astrological Hour of the Day)

- Joey Bujold

- Aug 14, 2025

- 4 min read

Muhūrta is the branch of Vedic astrology that concerns itself with the study of time, and the usage of that knowledge to produce a positive effect in life’s activities. In other words, it is the use of astrology to pick an auspicious time to launch a new endeavor.

The word Horā carries a number of meanings. It is etymologically connected to the two Sanskrit roots “Aho” and “Rātra”, the division of day and night. In Vedic astrology, one meaning directly relates to the division of a zodiacal sign, which produces the Horā chart (aka the D2), or second divisional chart of the Ṣoḍaśavarga system of Parāśara. It also corresponds to the division of time, roughly an hour. Horā is like a slice of time, and it is usually considered as 1/24th of a day or night.

Horā is a sūkṣma (subtle) counterpart of Vāra (the Vedic weekday) and cannot be examined without. One could make an analogy of the Vāra acting in many respects as a Mahādaśā, and Horā as the Antardaśā for Muhūrta calculations.

Just as there are many derivations of planetary daśās, one can break down the day into several hourly ways, for a number of uses. The intention of this article is to highlight some of the differences in its calculations and usages, both within the context as I’ve been taught by my mentors in the Jyotiṣa tradition of Śrī Acyutānanda Dāsa, and outside the lineage.

Calculation of Horā

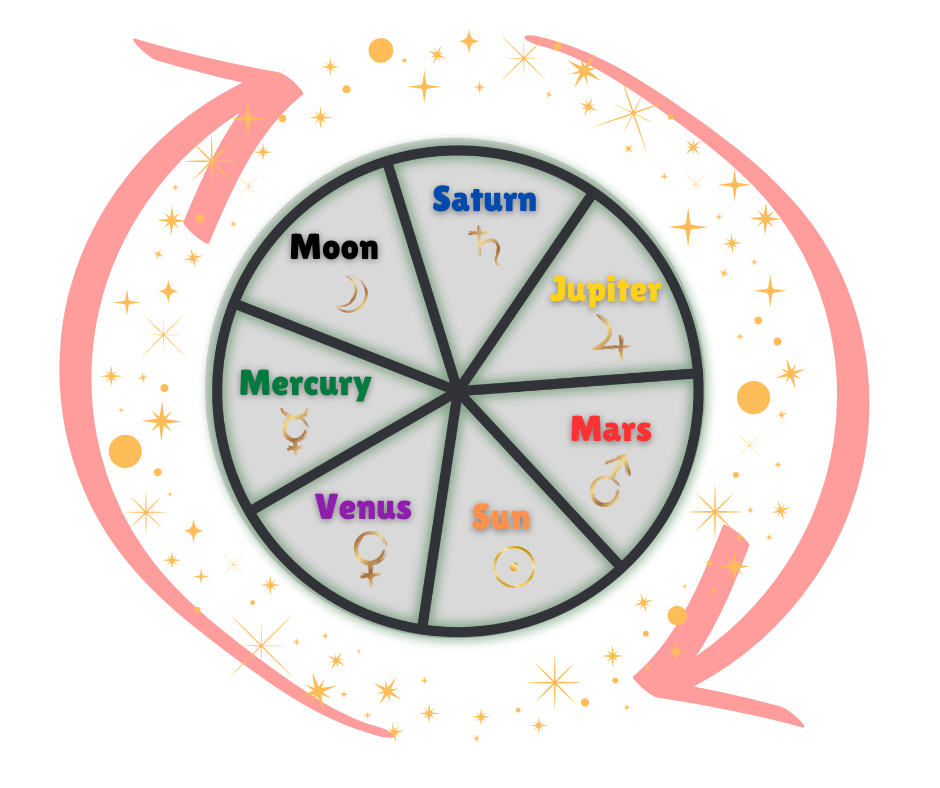

The primary concept to keep in mind is that in calculating Horā within any given weekday, we progress through the seven “bodied” planets (excluding the nodes) in a specific cycle over the course of a 24-hour period.

The Vāra Cakra is the planetary sequence which the Horās follow; this is fixed and does not change. The progression follows the slowest moving planets (from a geocentric perspective) to the fastest: starting with Śani (Saturn, 29.5 years to transit the zodiac), Guru (Jupiter, 11.9 years), Maṅgala (Mars, 1.9 years), Sūrya (Sun, 1 year), Śukra (Venus, 224.7 days), Budha (Mercury, 88 days), and finally Candra (Moon, 1 month).

Horā follows the light of the day, and as such, respects the Sun, as sunrise initiates the day, with some noted exceptions discussed below. In this manner, the starting anchor point of the Horās for any specific Vāra will depend ultimately upon a number of factors and the context of general usage.

In his comprehensive book (Jyotiṣa Fundamentals – My Master’s Words), my Jyotiṣa Guru and scholar Visti Larsen highlights the following table concerning Dinapraveśa (New daily ingresses):

Starting Time | Term | Usage |

Sunrise | Kālahorā | Natal Charts |

6 AM LMT (Local Mean Time) | Mahākālahorā | Muhūrta |

6 AM LST (Local Standard Time) | Mahākālahorā | Praśna |

Additional Context shared from my Mentors

Kālahorā calculation: This is the default Horā which I’ve found to be common in most Vedic astrology software packages (Deva.Guru, Śrī Jyoti Star, Jagannātha Horā) respects the sunrise and progresses from the anchor of the precise moment when the Sun rises in that locality. At that time, the Horā commences from the Vāra lord (e.g., Sun hour on Sunday at sunrise, Moon hour on Monday at sunrise, Mars on Tuesday at sunrise, etc.). The progression is divided into equal 1/24 increments (60 minutes each). Sunset is ignored here and the divisions are perfectly equal; only sunrise is anchored.

Mahākālahorā variations do not depend on sunrise or sunset as they are regarded as universal in nature and not connected to Bhuloka (the Earthly plane). They are said to pervade the entire manifested universe. They therefore attach themselves to the Vāra, independently of sunrise.

First variation: Before standardized time zones, each location used Local Mean Time (LMT), calculated from its longitude so that noon was when the Sun was highest locally. This variation starts the first Horā exactly six hours before local noon.

LMT is calculated by adjusting clock time according to exact longitude so that 12:00 LMT = the average time the Sun crosses your meridian throughout the year.

Example: Greenwich, England is 0° longitude, so their LMT is “Greenwich Mean Time” (GMT). Toronto is at ~79.38°W. 79.38 ÷ 15 ≈ 5.29 hours behind GMT. So when it’s 12:00 LMT in Toronto, it’s ~5 hours 17 minutes later in Greenwich.

This calculation identifies the moment of noon LMT, then goes backward exactly 6 hours before that point. This point becomes the start of the first Horā for that Vāra (e.g., Sun hour on Sunday, Moon hour on Monday, etc.).

This variation is used for general Muhūrta considerations.

Second variation: This is anchored itself to Local Standard Time and is used for Praśna (Horary) astrology, and is calculated in a similar way to the first variation (but with LST as the anchor point).

Yāmahorā: more common outside the lineage in calendrical almanacs and apps like Drik Panchang, compresses or expands the 12-hour cycles from sunrise to sunset and sunset to sunrise based on available daylight hours. Near solstices, day and night are uneven; near equinoxes, they are equal. Here, Horā follows both light and darkness, and is believed to influence planetary strength and weakness, ultimately tied to mortality. In the tradition, this is called Yāmahorā.

Practical Usage of Horā Calculation Methods in Deva.Guru Software

Open a DG session.

Click on the control toggle on the top right of the Pañcāṅga session.

Ensure your desired variations are turned on, including Yāmahorā, Kālahorā (LMT and LST).

In summary, the following points should be noted:

The default Horā setting cannot be turned off; it is used in Pañcāṅga analysis for Jātaka (natal astrology).

Kālahorā (LMT – Local Noon) is valid for Muhūrta elections.

Kālahorā (LST – Local Standard) is considered to be valid for Praśna.

Yāmahorā is also included for those astrologers and lineages who consider it as valid.

Ultimately, while my background and my bias as a student of Astrology leans heavily towards the centuries of accumulated knowledge stemming from what I’ve been taught via tradition, usage of any of these variations should be thoroughly researched by the astrologer to determine their efficacy for Muhūrta, or any other applicable usage. While traditions differ, understanding the differences in calculations allows for logical, context-specific application.

Om Tat Sat

.png)

Comments